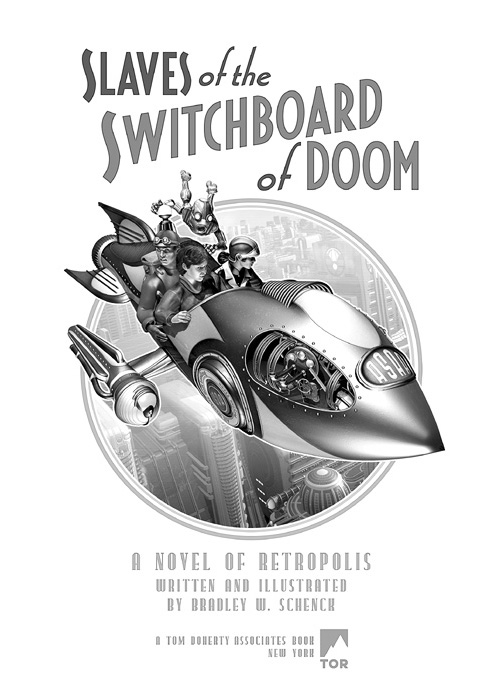

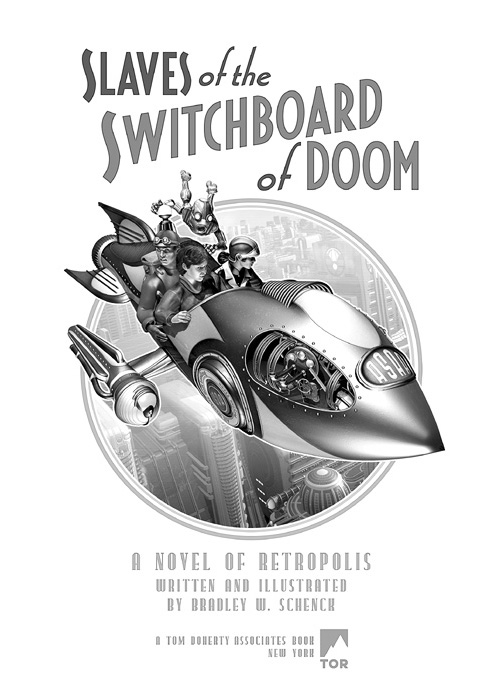

We’re just two weeks away from the release date for Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom. If you’ve been waiting, that may seem like a long time: but as you’ll see in this post I’ve been waiting for about five years.

So bear with me. It’s almost here.

Illustrating your own story is, mostly, a pretty great thing; it’s just that it’s more embarrassing when you make mistakes.

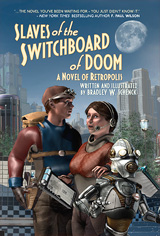

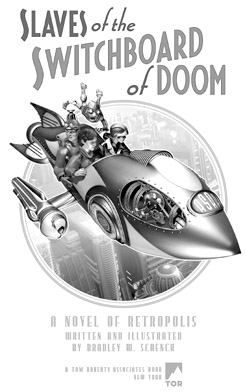

On the ‘mostly great’ side, I was able to work on my characters’ appearance while I was still figuring out who they were. The version of Dash Kent we see in the book was my second try. (Version One looked too old for Dash, and he didn’t have quite the right attitude.) Working on the character models was a big help to me during the early days of writing the book. I got to find out exactly how these people looked.

There are several characters who existed already, since they’d appeared earlier in The Lair of the Clockwork Book. Harry Roy, Maria da Cunha, and Mr. King all came from that story. Rusty was even older: I was working on him back in 1999.

But Dash, Nola Gardner, Thorgeir, Howard Pitt, Lillian Krajnik, and most of the other robots were all new. I built many of them while the story was taking shape.

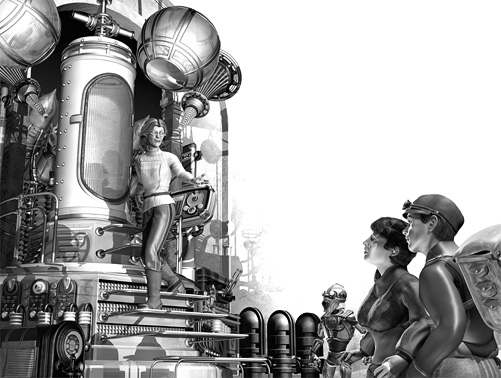

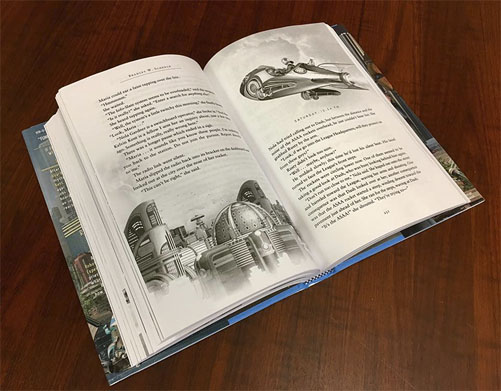

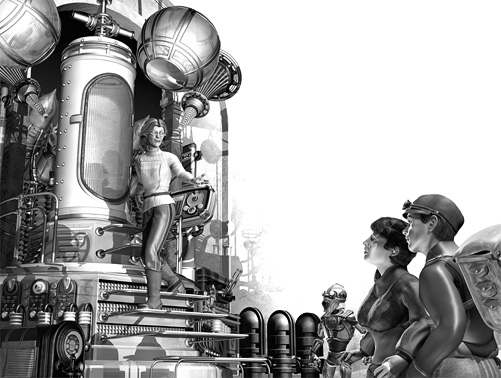

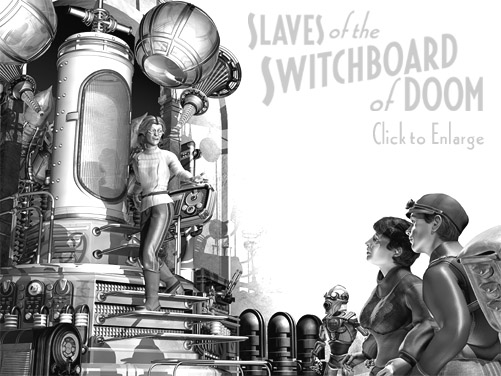

Once the first, and then the second, and then the third draft were behind me I was ready to start the illustrations themselves. I’m not quite sure when that was, honestly. Even the datestamps on the files don’t help me much; I can see that I created a bunch of folders on March 2, 2014, but that only tells me that I organized things on that date. I’m pretty sure the real beginning was some time in the previous December. The first one may have been this scene in Lillian’s laboratory, from Chapter 15.

I was creating just one illustration for each chapter this time – far fewer than I’d done in my earlier stories – and that meant picking That One Scene was always the first problem. Because there were relatively few pictures, one part of the problem was which characters were getting their chance to be featured. I was already planning the endpapers, where all the major characters would get a vignette; but I wanted them each to show up in the body of the book as well. So picking That One Scene could be complicated.

With that done, I came to the magical thing about illustrating your own work. Sometimes the scene in the picture was better than the scene in the text. And since the text was mine, I could change it. This happened several times. It’s a liberty you just can’t take with somebody else’s story.

On the other hand, there were times when the scene in the picture differed from the scene in the text… and I didn’t realize it. Finding those, and resolving the problems, was an ongoing task while I worked on the revisions to the book. And I know of one that was never fixed, a pretty big contradiction that I didn’t see until I was checking the galleys. It’s still there and, no, I won’t tell you where it is. Somebody’s sure to point it out to me, and then I’ll explain the Navajo philosophy about imperfections: they’re there so that wandering spirits have a way to get out of the work, if they should blunder into it and get lost.

This is a philosophy that can be pretty convenient.

There were times when avoiding a contradiction was pretty frustrating, though, since in an illustration you want to convey a sense of what’s going on but you can’t make visible things that shouldn’t be visible. That problem led me down a rabbit hole several times when it came to the first chapter. I think I did more versions of that one than any other, even though what you see in Chapter One is pretty simple. But… oh, the many layouts. The many changes. The many deletions.

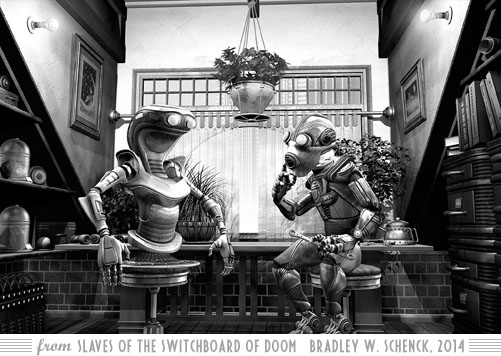

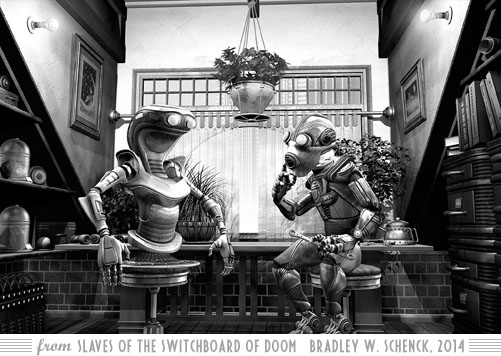

Rusty’s attic apartment, in Chapter Two, was pretty much the opposite. It was full of stuff, and I loved that stuff; but the picture wasn’t about that stuff. His books, his gadgets, and his collection of interesting mosses are all there, but they have to fade away behind the robots. There was even more stuff, out of frame. It saddened me that I had to leave it there.

Around the end of September, 2014 I finished my first pass through the illustrations for Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom. But I went back to revise them, and I did that more than once: there are three or four different versions of some of them. I didn’t lock them down until about a year ago. But at some point you have to realize that you’re done, and so around June of 2016 I admitted that I was done with these.

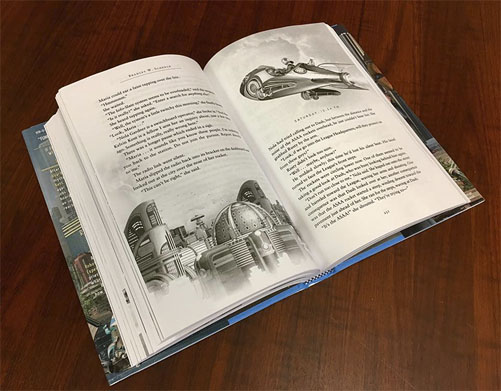

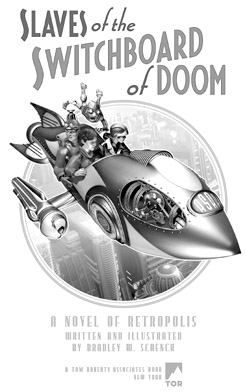

For The Lair of the Clockwork Book I created close to 130 illustrations, and that took far longer than it took to write the story; for Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom I made just twenty-four (counting the title page and the endpapers), and the story and its art took roughly equal amounts of time. That’s a much more workable ratio, if you ask me: and I was also able to spend a lot more time on each picture.

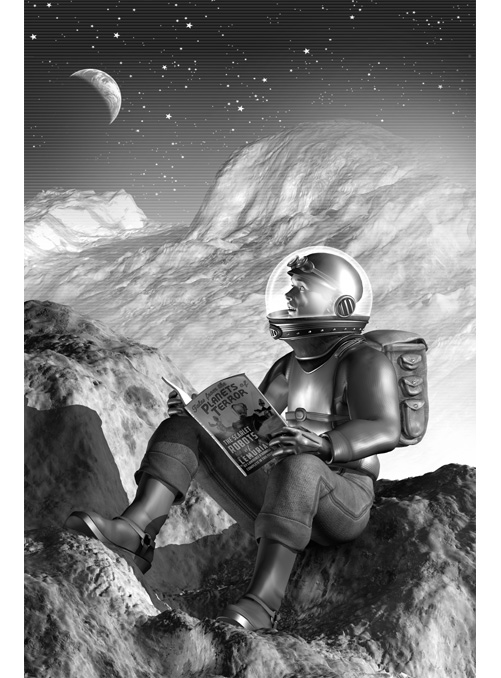

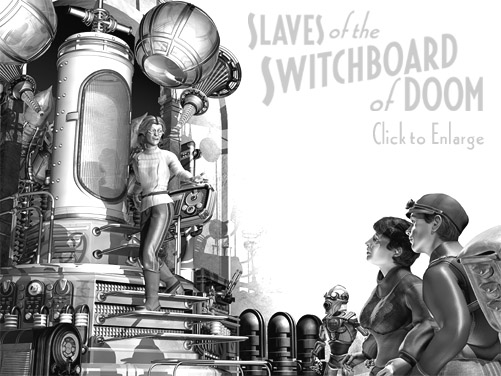

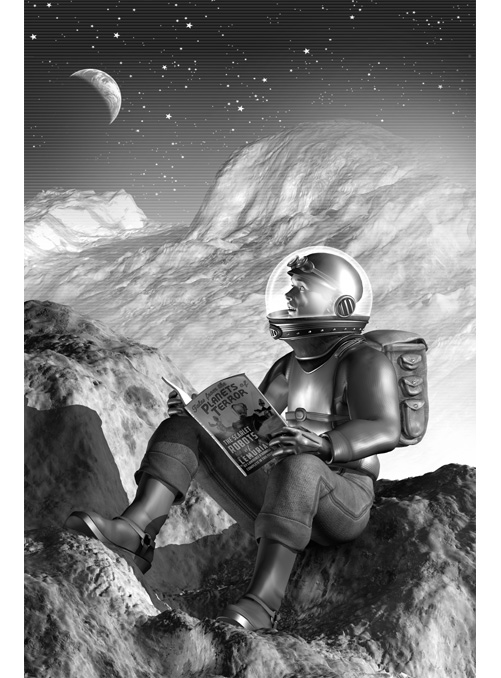

Among the differences I love in the new book is the way the text wraps around the illustrations, so like the illustrations in the old science fiction pulps. And the shift from color to greyscale, which was a purely practical decision, has pretty much the same effect. The art for the book evokes Dash’s approach to adventuring. He learned everything he knows from pulp magazines.

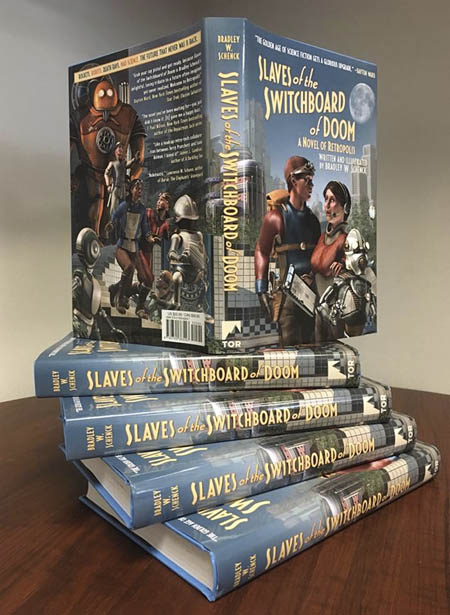

That’s not true of the publisher, though: you won’t find any of that yellowing, pulpy paper here. The paper chosen for the book is so wonderfully dense and white that the book weighs more than you’d expect. That’s especially surprising because the paper’s not unusually thick. But the book’s weight was the first thing I heard about it, and once I’d hefted one myself I tried to exhaust every possible joke about that on Facebook and Twitter.

But you can understand why, when you see how little ghosting there is from one page to its reverse – even when the art is dark. This is a book with what I call confident weight.

You’ll have your own chance to gauge its weight in just two weeks, on June 13. I hope you take that chance!

This entry was posted on Tuesday, May 30th, 2017

and was filed under Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom, Thrilling Tales of the Downright Unusual, Works in Progress

There have been no responses »

Here’s a round-up of news about Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom. There’s a new excerpt at the Tor/Forge blog, while the ten-book giveaway at Goodreads is winding down with just hours to go.

There’s also a preview of the illustrations and the book’s chapter titles.

And much to my own surprise (since I don’t have one yet) there are some photographs of the real, live, actual, printed book as it waits for your order.

And, well, everyone else’s order too. But mostly yours.

But first, a word from Publishers Weekly

One of the four big trades for book news and reviews has posted its very friendly review of the book.

The review starts with a description of the plot and a few words about the world in which the book takes place; then it ends with this:

“A genuine love for the material makes this a strong and entertaining debut.”

― Publishers Weekly

Like I said, friendly.

The GoodReads giveaway

As I write, the Tor Books giveaway for Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom ends soon. That’s less than sixteen hours from now.

So if you live in the United States or Canada you should dive right in and get in line. The odds are currently at 78 to 1. That’s way better than your chance of being struck by lightning.

An excerpt from the book

This just appeared at the Tor/Forge blog: it’s an excerpt from the book’s first chapter.

You can do some mental composition here by combining the excerpt with the Chapter One illustration in this other, different preview post at the Tor.com web site. Can’t you?

Yeah, I forgot one

That’s right. I just referred to the Tor.com preview post, which shows several of the book’s illustrations and calls out its pulpy chapter titles. Like “Return of the Plumber of Prophecy”, which is really does describe what’s happening in the chapter.

Anybody who’s experienced a Plumbing Emergency can tell you that plumbing is of vast (and perhaps galactic) importance.

Pictures of the book

I may have saved the best for last, here, or maybe the sight of these pictures is just so strange, five years after I started the book, that I don’t quite know what to think about them.

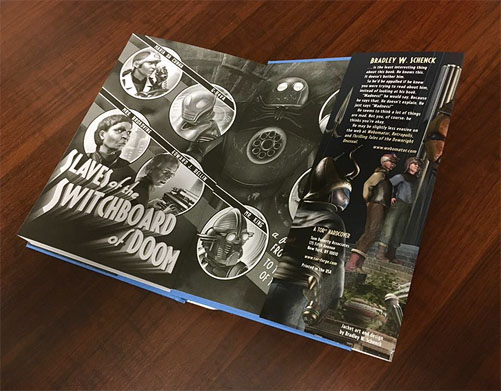

My editor posted these shots last week. You can see a stack of the real, final, printed books:

And the book opened up to one of its two-page spreads:

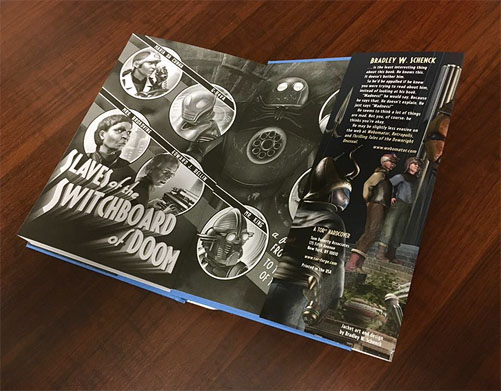

And, finally, a view of the book’s second endpaper:

Aaaaaaaaand that’s it for today. Remember, Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom will be available in all the usual places on June 13, just one month from now.

This entry was posted on Monday, May 15th, 2017

and was filed under Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom, Thrilling Tales of the Downright Unusual, Works in Progress

There have been no responses »

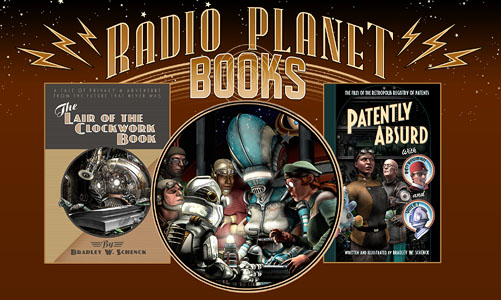

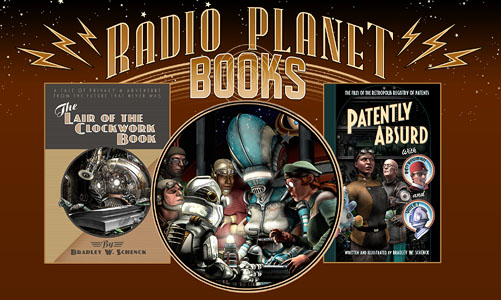

The Radio Planet Books web site is now alive and kicking.

I did a bunch of work on this late last year and at the beginning of this one; then I worked on it again through March, and picked it up one more time in early May.

Radio Planet currently has a slim list of one, count it, one book: the eBook edition of The Lair of the Clockwork Book. At the moment you can buy that title directly from the Radio Planet Books web site (as well as at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Kobo).

But even though there won’t be news about a second book until some time this summer, there is still more at the site than you’d suspect.

That’s because this site is rich in secondary content like page animations, dynamic sidebars, and other content that changes depending on the kind of page you’re looking at. So it’s the very broad foundation for what is, today, a very narrow thing: it’s kind of like I built the Great Wall of China so I’d have a place to put my Eiffel Tower.

This site adapts itself dynamically to the width of your browser window. That helps it to be readable on just about any device.

But because everything is indexed to the window’s width you can see the same changes happen on a large display, every time you resize your browser. The elements on the page rearrange themselves, the size of the type changes, and some elements appear or disappear, all depending on changes to the window’s width. The crazy amount of Javascript I’m using to control all that ate up a large amount of the time I spent on the site; but that was pretty near the beginning. Filling out the sidebars and footers, and creating the animations, was a large part of the remaining time.

The thing likeliest to change at this point is the home page copy. I wrote that last, as I usually do, and what’s up there now is only the second version. There will probably be a couple more before it all settles down.

But, more importantly? More books. Expect to see news about my Patently Absurd here, and at Radio Planet, in a couple of months. There’s also another project that I haven’t been able to talk about, because nothing’s settled: an illustrated book of stories by someone other than me. But negotiations have dragged on for such a long time now that I’m not even sure where that one’s going. It’s a case where you and I might be equally surprised, later this year.

This entry was posted on Thursday, May 11th, 2017

and was filed under Web Development, Works in Progress

There have been no responses »

It’s hard to say exactly why popular culture settled on the mad scientist as an essential ingredient for stories that look science fictional. The wild-haired, cackling inventor who meddles in Things That Man Was Not Meant to Wot Of could just as easily have been a lawyer or an accountant. Because lawyers and accountants meddle in Things That Man Was Not Meant to Wot Of every day, and you can measure their success by whether or not anybody Wotted Of what they were doing.

Though I guess that’d be a different kind of story.

Me, I’d enjoy a story about wild-haired, cackling accountants. But the zeitgeist has spoken: mad scientists are the thing.

So when I set myself to building the city of Retropolis I had to do something about mad science. My solution was twofold.

First, I made it big. Big to the point where, in this world, all science is mad. There’s just no such thing in Retropolis as a careful, methodical researcher who slowly extends the limits of our knowledge through carefully designed and controlled experiments, complete with double-blind studies and peer review.

If you even suggested that to a Retropolitan scientist, you’d get a wild-haired cackle and you’d find yourself floating in a vat of something you’d rather not think about.

So that was number one. Make it big.

Next you have to wonder how a society would deal with Big Mad Science. And there are a lot of things there to consider.

Because there are benefits to Big Mad Science. Sure, you get a lot of explosions and unfortunate by-products from these inventions, like mutations, and huge poisonous clouds, and flying squids. But you also get rapid advances in every discipline, from Robotics to Fluid Mechanics to (my personal favorite) Defensive Botany.

My City of Tomorrow is practically defined by its Big Mad Science. So the people who live there must have developed a system that encourages this kind of research while protecting the civilians from its side effects. And they did. They created the Experimental Research District. It works like this:

The District represents one successful approach to innovation.

If you take every wild-eyed scientist with a lab full of explosively inventive progress and then shove them into the same small neighborhood, it was argued, they would tend only to hurt themselves, each other, and their assistants. There would always be civilian casualties, of course: but it was so much easier to keep those to a minimum if the threats were all crowded together. The apparent danger of one immense, coordinated incident was considered small because the occupants of the District tended toward self regulation of the kind that starts with ‘Fenwick’s project may be more remarkable than mine!’ and ends with ‘Good old Fenwick. When shall we see his like again?’

The Air Safety Association has a special squad trained to deal with the District. That training, although Bonnie did not know it, was concentrated in a very large, top secret manual entitled Things We Have Run From, and How To Run From Them.

– from The Lair of the Clockwork Book

But of course this raises the question of how you can round up all these mad inventors so you can confine them in one part of the city. The answer there is to get ’em when they’re young.

The Retropolis Academy for the Unusually Inventive is the only place in the city where students can study science. Oh, there are plenty of engineering schools, plenty of general universities, and many, many schools for younger students. But any students in those other schools who start to show the telltale signs of a scientific mind are swiftly transferred to the Academy.

They might escape notice when they memorize the Periodic Table; they can easily slip by if they tinker with the chemicals in a chemistry lab; but the moment they build their first Antimatter Catapult or High Energy Squirrel Emulsifier, their teachers pull them out of class and pack them off to the one school that’s prepared to deal with their particular talents. Once they arrive they’re on a fast track program that will one day release them into the Experimental Research District – the only place in Retropolis, by statute, where scientific research can be pursued.

Having entered the Academy there was, normally, only the one outcome: a lifelong career in the middle of the explosions and the sometimes successful transmogrifications that punctuate both the District and quite a few of the careers we just mentioned, with punctuation marks like the period, the exclamation mark, and, now and then, the question mark. In careers of this type, an ellipsis is extremely rare.

– from Fenwick’s Improved Venomous Worms, in Patently Absurd

You have to applaud the kind of ingenuity that lets a society adapt to both the blessings and the curses of its Big Mad Science. The zoning regulations of Retropolis were well thought-out and perceptive; the education system works hand-in-hand with those regulations; and as a result the citizens of Retropolis are relatively safe from the side-effects of Mad Science, while they’re still able to enjoy its benefits.

And if the system seems a little bit crazy to you or me, we have to remind ourselves that it’s their response to a crazy situation. If we take a good, piercing look at our own situation, and the systems we’ve put in place to adapt to it, we may find that we’re not in a position to judge.

This entry was posted on Monday, May 8th, 2017

and was filed under Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom, Thrilling Tales of the Downright Unusual, Works in Progress

There have been no responses »

Let’s say you have a massive megacity, partly lighter than air, filled with personal rocket ships, intelligent robots, and public transportation that’s both sensible and universal.

That’s not a hypothetical proposition. You can have one. I’ve got one. It’s the city of Retropolis.

“Oh,” you say, “that doesn’t count. It’s imaginary.”

“That hardly matters,” I reply, “when I know that you’re an imaginary commenter.”

And you fall silent, so I continue.

I invented Retropolis around the end of the last century. And I’ve spent quite a lot of time there. I began to set stories in my City of Tomorrow about three years before I started tinkering with Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom: but they were short, or at least short-ish, stories, and in a short-ish story you don’t have a lot of room for the details and fiddly bits that are essential when you’re working on something as long as a novel.

In a novel you have to worry a lot more about how all this stuff works: the stuff that’s not important in a short-ish story because it falls outside the scope of what must be known in order for the story to make sense.

One of the biggest fiddly bits was the robots of Retropolis.

Retropolis has a lot of robots. They’re everywhere. And although they are clearly not human people, they are people. They’re just a different kind of person.

Still, making a robot is completely different from making a human person.

“It’s not as much fun,” you interject.

But I have lost patience. “Stop doing that. People are staring.”

In practical terms, a new human’s expense is pro-rated across a couple of decades; a robot’s expense comes completely, and sizably, at the beginning.

Making a robot is an investment. So who’s investing?

That was the question I had to answer. Now, I want to emphasize that I wasn’t looking for a great system. I wasn’t even looking for a good system. What I wanted was a kind of system that human people would think up when faced with this problem.

That’s why I settled on indentures. We’ve used them before.

You don’t buy a robot in Retropolis. You just pay for its production. Then that robot is required to work for you, at a certain rate, until its indenture has been paid. Once the robot’s paid off its indenture it becomes a free agent, able to continue working for you (for wages), or to quit its job and work for somebody else, or to set up as a freelancer and work for lots of different people.

Like all systems this sounds great on paper, especially to the person who dreams it up. And to everybody else, once it’s established, it becomes the system. Somebody’s designed the system. Somebody’s made sure the system is fair. And, since it’s established, we no longer have to think about the system. It’s just the way things work. And that’s the way we work, once we decide that a system is handling a problem for us.

Retropolitans are pretty good with systems, and they run their city pretty well, so if you’re going to have an indenture system it’s a good idea to run it fairly, the way they do.

But indentures aren’t perfect. There are lots of ways they can go wrong. And the incentive for making them go wrong is pretty compelling, since it involves making loads of money.

Student loans are a kind of indenture. Any kind of debt can be a form of indenture, once the lender is able to garnish your wages. If you give the indenture holders the ability to change the rules at any time, an indenture may never end: there’s just so much money to be made, if they never end. And an indenture that never ends? That’s slavery.

I remember how horrified I was, once, when I learned that – not fifty miles from my own home – there was a farm where illegal immigrants were saddled with the cost of their travel to the United States, and then forced to work for the farm that had bought that debt. They had to live on site and work, in terrible conditions, while they were charged high rates for their lodging and food. This was an indenture system that was designed to keep those laborers indentured forever. It’s a terrible system that we’ve invented more than once, and which we sadly continue to invent. I’d guess that the people who cook up these schemes often think they’re doing it for the first time. But they’re not. We’ve done the same thing over and over again.

So an indenture system, despite its built-in risks for corruption and abuse, is exactly the kind of system we’d be likely to come up with when it comes to intelligent robots.

Fortunately for the robots of Retropolis, the city has a pretty responsible system. There’s oversight; there are penalties; and once they’ve paid off their indentures the robots are free people, just like human people. The robots themselves have formed the Fraternal League of Robotic Persons, and one of the League’s main functions is to pool member dues to help robots pay off their indentures.

But there’s always the possibility that things will go wrong.

If you build your own robots in a place that’s not known, not regulated, you can simply not tell your robots about indentures, or about freedom: they’re in your power. At that point you appear to own the robots themselves. At that point, you’re building slaves.

Here’s an embarrassing fact. It wasn’t until I was working on the book’s third draft that I realized the League system for paying off indentures is a lot like the system used by the Discworld golems. They aren’t exactly the same: the golems are considered property, so Pratchett’s Golem Trust purchases them outright and then makes them their own owners. But they are pretty similar.

All I can say there is that this Pratchett fellow was pretty smart, and so he got there ahead of me.

The best news of all for the Retropolitan robots is that the system of indenture may be coming to an end. They have a new President over there, and he has long-term plans for robot production that aren’t known to the human people of the city.

His plans aren’t secret. It’s just that the human people, content that they have a system in place, aren’t very curious about what the League is doing.

This entry was posted on Monday, May 1st, 2017

and was filed under Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom, Thrilling Tales of the Downright Unusual, Works in Progress

There have been no responses »